When Getting Sober Reveals an Underlying Illness

Photo by Saneej Kallingal on Unsplash

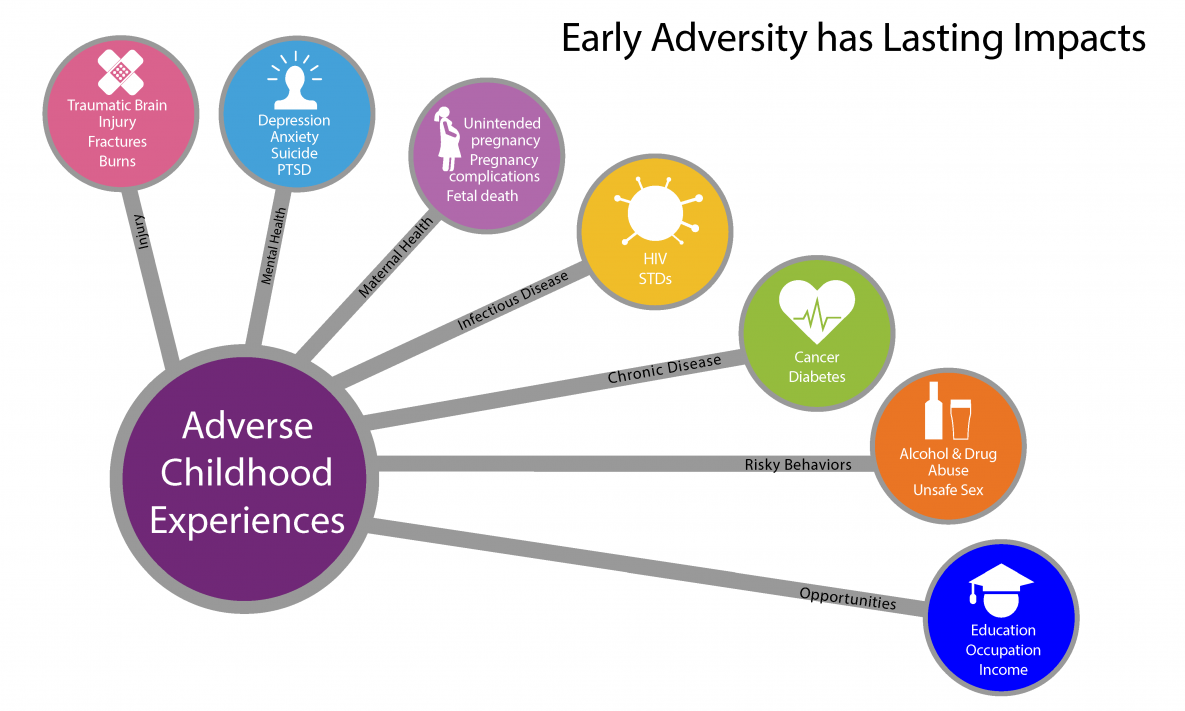

People who have had multiple traumatic events (adverse childhood experiences) in their youth are more likely to suffer from chronic illnesses, alcohol use disorder, and more in adulthood.

One reason we get chronic illnesses is from the effects of stress on our bodies, and adverse childhood experiences create a lot of stress.

Getting sober is often considered the ultimate solution to our problems. In many ways, it is: we stop the behaviors that led to the self-destruction to our bodies, our relationships, and how we live our lives. We wake up without feeling hungover or in withdrawal from drugs we’d taken the night before. By dealing with the issues that led to using, we begin to experience healing and generally feel better.

But for some of us, that isn’t enough. Physically, we can actually feel worse after we stop using or drinking. We may discover that drugs and alcohol were masking the symptoms of a serious and deeply rooted illness.

Discovering My Autoimmune Condition

When you get sober, it usually isn’t all pink fluffy clouds and going about your day with a spring in your step. For me, in addition to the struggles of early sobriety, I’ve had to deal with something much greater: I’ve spent the last seven years with chronic fatigue so bad that many mornings I struggle to get out of bed — sometimes every day for three months at a time — and, at times, I have so much pain in my body that it hurts to even move my toes.

I have an autoimmune disease — a condition in which the immune system mistakenly attacks the body’s own tissues. Some of the more commonly known autoimmune conditions include Type 1 diabetes, lupus, psoriasis, rheumatoid arthritis, celiac disease, and Crohn's disease.

And I, along with many others in recovery, suffer with a chronic and sometimes life-threatening condition that has a strong link to our childhoods.

For years my autoimmune condition went undetected. I was told that its recurrence each year — with symptoms including chronic fatigue, aches and pains, low energy, lack of motivation to do anything apart from sleep and lie on the sofa — was simply an episode of depression. My doctor would sign me off work for a month. Doctors ordered rest and gave me a prescription for increasing doses of antidepressants. Invariably, after a month off, I’d get better. I had no reason to question the doctor’s advice because I was improving with their prescribed course of action.

Then I moved to a new country.

Moving to America caused a profound amount of stress both mentally and physically. I had to start my life over in an unfamiliar place. I launched a new business as a full-time writer and consultant, built a new life, and developed a new community of support. I didn’t have the luxury of paid leave or intensive medical care.

Around this time, my fatigue became chronic for much longer periods than before. I’d get up at 8 a.m. and have to take a nap by 11. It was very challenging to function. I also started to suffer with chronic pain throughout my body, shooting nerve pain and numbness in my arms and legs, loss of strength, reduced thyroid function, degeneration of my teeth, weight gain, intestinal and digestive issues, chronic headaches, inability to focus, unexplained rashes and bruises, and abnormal blood work. I felt as stiff as a 90-year-old, not a 39-year-old.

I had a dilemma: I could only work for short periods of time, but I wasn’t able to stop working because I had to support myself.

For the last two years I’ve tried to determine exactly what’s been going on in my body. After many doctor visits, I was finally taken seriously enough to be referred to specialists for suspected multiple sclerosis, rheumatoid arthritis, or lupus. None of these conditions have a great prognosis, particularly MS, but it was a relief to finally be taken seriously after a lifetime of being dismissed, told I’m a hypochondriac, or diagnosed with depression. Only the coming months will tell exactly what I have and how to move forward.

Being the curious person I am, I wasn’t able to just accept the fact that I had an autoimmune condition. I had to understand why I had it. Through nearly two years of therapy and by doing intensive research, I now understand the strong psychological link between my childhood and my sickness.

The Link Between Childhood Trauma and Adult Illness

Autoimmune conditions are more prevalent than you might think. They affect 23.5 million Americans, nearly 80 percent women. But why? And why do so many of us in recovery discover when we stop using that we have unexplained physical sickness?

Simply, and more often than not, the answer is to be found in our childhoods. Gabor Maté, in his book When the Body Says No: Exploring the Stress-Disease Condition, talks extensively about the role of our childhoods on our ability to deal with stress, emotion, and sickness in later life. He believes it is crucial that we are taught these coping strategies and that we receive sufficient support in our upbringing.

“Emotional competence requires the capacity to feel our emotions, so that we are aware when we are experiencing stress; the ability to express our emotions effectively and thereby to assert our needs and to maintain the integrity of our emotional boundaries; the facility to distinguish between psychological reactions that are pertinent to the present situation and those that represent residue from the past,” Maté writes.

He goes on to say, “What we want and demand from the world needs to conform to our present needs, not to unconscious, unsatisfied needs from childhood. If distinctions between past and present blur, we will perceive loss or the threat of loss where none exists; and the awareness of those genuine needs that require satisfaction, rather than their repression for the sake of gaining the acceptance or approval of others. Stress occurs in the absence of these criteria, and it leads to the disruption of homeostasis. Chronic disruption results in ill health.”

I had a very stressful childhood growing up in a household with substance misuse. I relocated to the UK at just three years old and started a new life in a single-parent family. I didn’t have the emotional support and attention that I needed, I suffered terribly from my father’s abandonment, and consequently I developed maladaptive coping strategies: eating disorders, smoking, and addiction.

My story is no different from those of millions of others in recovery. The vast majority have had adverse childhood experiences.

See a larger version of this image here.

The Adverse Childhood Experiences Study

One reason we get chronic illnesses is from the effects of stress on our bodies, and adverse childhood experiences create a lot of stress. These experiences include physical and or emotional neglect, parents’ substance use and mental illness, loss, abandonment, divorce, humiliation, and other types of abuse. Doctors Vincent Felitti and Robert Anda performed a large-scale study on these types of traumas, known as the Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs) study.

Their results were profound. Felitti and Anda were able to predict the effects of ACEs on long-term health:

64 percent of the population have at least one ACE

12 percent have a score of four ACEs or more

Those who experienced ACEs are at a higher risk of autoimmune conditions

Having a score of four or higher:

doubles the chance of heart disease

doubles the chance of becoming a smoker

increases by seven times the likelihood of to developing alcohol use disorder

increases the risk of suicide by 1,200 percent

increases the risk of depression by 460 percent

doubles the chance of being diagnosed with cancer

For each ACE experienced by a woman, the risk of being hospitalized with an autoimmune condition rises 20 percent

A male with a score of 6 or more has a 46-fold (4,600 percent) increase in the likelihood of becoming an intravenous drug user

Source: The Origins of Addiction: Evidence from the ACE Study, Vincent Felitti, MD, 2004

Felitti concluded that adults were — largely unconsciously — using psychoactive drugs to gain relief from childhood traumas. However, he says, “Because it is difficult to get enough of something that doesn’t quite work, the attempt is ultimately unsuccessful, apart from its risks.” He continues, “The prevalence of adverse childhood experiences and their long-term effects are clearly a major determinant of the health and social well-being of the nation.”

In my own experience, and the experience of many in recovery, once we remove the drugs, we remove the anesthesia from our adverse childhood experiences. So many of us reach for other addictive substances to cope: relationships, food, smoking, excessive exercising. The reality is that nothing really works. The pain only gets worse, and this is frequently when we discover we have autoimmune conditions.

So what is the answer? Felitti says, regarding our traumatic childhoods: “Taking them on will create an ordeal of change, but will also provide for many the opportunity to have a better life.” For me, that means taking good care of my physical and mental well-being: trauma-focused psychotherapy, regular exercise, sufficient sleep, outdoor activities, community, alternative medicine, and referrals to specialists who can help treat the symptoms I am experiencing.

The longer that I am in recovery, the more I realize we have more to recover from, and our childhoods are at the very heart of that pain.